Secondary Dominant: An Ode to David Bowie

Eric Strom

The article Secondary Dominant: An Ode to David Bowie, written by Eric Strom, originally appeared on Pop Music Theory, a website where you can learn music theory using popular music examples.

I got the news as soon as I woke up on Monday morning. David Bowie had passed away.

It goes without saying that David Bowie was an extraordinary and influential artist. Over the past week, many articles have been published celebrating his life and boasting his many achievements, which includes selling over 140 million albums. Here at Pop Music Theory, we are going to honor this great man in our own special way – by learning about secondary dominants using David Bowie’s “Starman” as our example.

Although secondary dominants are an advanced topic, I am going to try to present this information in a way that anyone with basic music knowledge can understand.

Before you begin this epic post (complete with audio excerpts), you may want to listen to David Bowie’s “Starman” in full. Here is the song in it's entirety:

David Bowie’s “Starman” was recorded and released in 1972, and was included on the concept album

“The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.” The song has been widely acclaimed.

Let’s Start at the Very Beginning

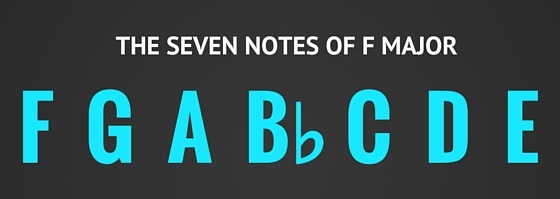

Songs in a certain “key” are generally made up of certain notes that belong to that key. “Starman,” for example, is in the key of F major. Here are the notes that belong to F major:

do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti

Notice that out of the seven notes that belong to F major, only one of them has a flat. That’s why you will hear a musician say something like “We are in F major… one flat!”

If a Song is “In a Key,” What Does that Mean?

When we are talking about tonal music – whether that be a David Bowie song or a Mozart piano sonata – musician’s often say a song is in such-and-such key, like F major. So, what does that actually mean?

- Being “in F major” means that that song is generally only using the notes that belong to the key of F major. We already talked about the seven notes that belong to F major

- Being “in F major” means that the composer has used harmony to indicate that the note “F” is the tonal center of the song.

Helpful hint: Using the notes that belong to F major is not enough to establish “F” as the key (D minor, for example, uses the same notes as F major). Harmony needs to also be used to establish that “F” is the tonal center.

Harmony is what results from the interaction of two or more notes. Over centuries of tonal music, certain patterns and rules of harmony have emerged.

A Brief Introduction to Diatonic Triads

Remember our seven notes that belong to the key of F major? Well, below are chords that are made out of ONLY these seven notes – what we call diatonic triads. Think of diatonic to mean those notes that belong to the key.

Diatonic Triads in F major. Just remember: Major-minor-minor-major-major-minor-diminished

To create these diatonic triads, we take each of the notes that are in our key, and upon each of them we add two thirds. For example, starting with our F note, we add another note which is a third above that (A), and then a third note which is another third above that (C). We repeat this process for each of our seven notes in F major.

These diatonic triads are some of the chords that we might see in our David Bowie song. (Allow me to foreshadow what is to come: Sometimes a song might use notes that are NOT in the F major scale. When this happens, it naturally challenges our ear and creates color and interest.)

Important Side-note: What is a Third?

In our key of F major, remember that our notes are F, G, A, B♭, C, D and E (in that order). The interval between F and G is a 2nd, between F and A is a third, between F and B♭ is a fourth, and so on. Interval is defined as the distance between two notes.

We will be getting MUCH deeper into the subject of triads another day. Let’s move on to our final foundational concept before we get into our topic of the day – secondary dominants.

V to I – A Progression that Sounds Correct and Natural

I mentioned before that there are certain “patterns and rules” in harmony – well, there are many, and we will cover more of them over the weeks to come – but let’s start with just one. Take a look at the diatonic triads again, and note two of the chords:

The dominant: A Major chord built on the fifth scale degree. The tonic: A major chord built on the first scale degree.

Here is one of our rules:

When we hear the dominant chord (the V chord), it naturally leads the ear to the tonic (the I chord).

If you have listened to enough tonal music, whether that be David Bowie or Janet Jackson or The Microphones, your ear has been subconsciously trained to hear a V-I progression as natural and correct.

(This is true even if you are not AWARE of it. Consider someone who is a casual, everyday listener to music – someone who cannot identify chords or chord progressions. Even for this individual, this V-I rule has been subconsciously embedded into their mind.)

In fact, in our David Bowie song “Starman,” the V resolves directly to the I chord 12 times! (Granted, several of those times are in the “outro” section). Over the years, I’m guessing I’ve personally listened to the song “Starman” at least 20 times. That means that just from listening to this one song, I’ve been exposed to the V-I chord sequence 240 times. Talk about brainwashing!

Secondary Dominants: Capitalizing on the V-I Instinct

The instinct for V to resolve to I is so strong, that songwriters are able to capitalize on this – using it as a tool to temporarily break away from the key (which, you may remember, adds color and interest).

So, What is a Secondary Dominant?

A secondary dominant is when you play a chord which is a temporary, almost “pretend” dominant (V Chord) which will resolve to a diatonic chord which is our “pretend” tonic (I Chord)*. Here’s a chart:

V/ii chord, which is our “pretend” dominant, resolves to the ii chord, our “pretend” tonic

*Important side-note: Sometimes secondary dominants do not resolve to the chord of which it is the dominant. We will save this for another lesson.

To really understand this, let’s finally take a look at “Starman,” our David Bowie song, so we can see a real life example.

David Bowie’s “Starman”

Here is a 0:22 second clip from “Starman” – an excerpt of the chorus. Listen to the clip by clicking the play button – and follow along with the lyrics below:

“There’s a starman waiting in the sky

He’s told us not to blow it

‘Cause he knows it’s all worthwhile

He told me

Let the children lose it

Let the children use it

Let all the children boogie

(Lyrics from David Bowie’s “Starman”)

After listening to that clip you are probably thinking:

– Wow, David Bowie is amazing.

– Where is this supposed secondary dominant of which you speak?

Below I will be presenting a chart that will really break it down. But first, let’s explain something. In the chart below, along side each lyric will be some different information. First, the name of the chord that is playing during that lyric (for example, F major) and second, the harmonic analysis. Whoa! Sounds fancy! What’s that?

The harmonic analysis is when we listen to a song, and do our best to analyze what harmony has emerged from the instruments that are playing within the song. It is written out in roman numerals, which represent each chord. UPPER CASE represents major chords, and lower case represents minor chords.

Really important side-note: Harmony is not always created by multiple notes being played at the same time (like the strumming of a guitar chord for example). Sometimes, harmony is created over time by a single instrument playing notes consecutively. Also, multiple instruments blend together to create harmony (like in “Starman”). It can become confusing at times!

The Chord Progression (and Harmonic Analysis)

Back to our example. Let’s listen again to our short clip, and this time, follow along with the graphic below. Click the play button to begin:

The gray arrow indicates our secondary dominant, which is a V/ii resolving to a ii.

The gray arrow in the chart above points out a very interesting chord, D major. If you take a look at our diatonic triads chart above, you will see that the six chord in F major is supposed to be D minor, not D major. This D major is our secondary dominant.

The D major chord acts and sounds as if it is a “pretend dominant” to the ii chord (G minor), leveraging the strong instinct for five to resolve to one. The D major then resolves to the G minor chord, which is the chord of which it is a dominant. This role/context allows for and smooths out the D major chord – which would otherwise be wacky and out-of-key-signature. As previously stated, as a non-diatonic chord, the D major adds color or interest to the song.

Also, because of the voicing of the chords, the raised F, (F♯) in the D major chord, makes for a “walking up” effect from F, to F♯, to G.

Bonus Music Theory Topic: Minor iv Chord

Earlier we spoke about adding interest to a song by using notes that are not in our normal key. Notice the B♭ minor chord in the chart above during the lyric “children lose it.” The B♭ minor chord, with it’s D♭ in the third, is certainly not in our normal key of F major. If you take a look back at our diatonic triads chart, you will see that we are “supposed” to have a major IV chord.

When you are in a major key, and a minor iv is used, it is a very dramatic and potent chord. It is a great chord – but if you are a songwriter, you should be careful not to overuse this chord in your songs.

We will stop here for now – as I am planning to write a full post about the minor iv chord, where it comes from and how it is used in songs. So, stay tuned for that!

Other Secondary Dominants

Today we saw an example of the secondary dominant V/ii. Here is a list of other common secondary dominants: (not an exhaustive list)

- V/V (very common)

- V/vi

- V/iii (personal favorite)

- V7IV

I am absolutely in love with secondary dominants. So, you can be 100% sure that I will eventually post examples of each and every one of these different types of secondary dominants.

More information about secondary dominants:

- Harmonic Functions : Secondary Dominants

- We also have secondary dominants construction, identification and ear training exercises

©2016 Eric Strom. Published by teoria.com